Indian Agent |

"He's arrived, sir."

James McLaughlin turned from the second story window of the white framed building overlooking the Missouri River valley. McLaughlin had already known he had arrived. He had watched the solitary man and horse slowly approach from the south. He always did ride slowly, McLaughlin thought. Come to think of it, near all Indians ride slow these days. Hasn't always been that way, of course. It was McLaughlin's job to watch the mood of the people -- and he was good at it. Buffalo hunts were a thing of the past -- the last of the buffalo were gone about ten years ago. So these days, an Indian on horseback in a hurry meant trouble for the reservation -- trouble for the government -- trouble for McLaughlin. But the stubborn, cautious Indian downstairs always did ride slowly now. When he was young, this same Indian was the fastest, most skilled hunter and warrior. But not now. He hadn't personally ridden in the raids against the army for many years either. His plans for attack were carried out by his braves like White Bull and Crazy Horse, who would use speed and surprise to kill. McLaughlin pictured his visitor downstairs controlling his people with long powerful strings, rather than using fast horse.

|

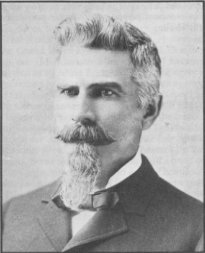

Major James McLaughlin 1842-1923 was born and raised in Avonmore, Ontario Canada. He moved to Mendota, Minnesota and became a U.S. citizen at age 23. For several years, he worked as an itinerant blacksmith and salesman. In Mendota in 1864, James married Marie Louise Buisson who was one-quarter Sioux. In 1871, he was hired as a blacksmith at Fort Totten, Devils Lake Agency, Northern Dakota Territory but was trained to be an Indian agent. He was officially appointed agent in 1876 and was transferred to the Sioux reservation in the Dakotas at Standing Rock Agency in 1881 where he was Indian Agent until 1895. He strove to make the Indian self-sufficient by encouraging them to become educated and adopt white traditions. |

It was Major James McLaughlin's job to cut those strings. McLaughlin truly thought that if he could keep him out of the picture -- to continue to curtail his power -- the assimilation of the Indians would be completed that much sooner. As Senator John Logan said, "... make them as white man."

But McLaughlin's attempts to demonstrate to the Sioux that their old hero was powerless to lead them or help them had no effect whatsoever on his popularity. All visitors to the Standing Rock Reservation, Indian or white, wanted to meet the man downstairs. To many people he was a great leader, a prophet, a legend. To James McLaughlin he was a constant symbol of Indian resistance, a continual defender of the Indian culture that the government was determined to eradicate. If only there was a way to permanently remove him from the reservation...

McLaughlin gestured with his right hand holding the burning cigar towards his aide and interpreter. "Yes, Louis. Bring him right up." Louis Primeau had been the agency's interpreter for going on seven years now. McLaughlin's fluency in Lakota was somewhat limited and Primeau was a great asset. "And as usual, Anson will be needed." Anson Fry was McLaughlin's aide and stenographer.

"Yes sir." Louis descended the wooden stairs of the agency's headquarters. McLaughlin seated himself at the large pine desk in the middle of his office. Soon, his guest entered the room, followed by Louis and Anson.

"How," said McLaughlin while standing and raising his right palm to his visitor.

Sitting Bull stopped close to the doorway and surveyed the room with unblinking intense eyes. His stoic weathered face displayed no emotion, his gaze now focused on James with dispassionate familiarity. Sitting Bull raised his hand slightly and gruffly uttered, "How, White Hair."

"White Hair" was what the Sioux called Major James McLaughlin. McLaughlin gestured to the middle of three chairs in front of his desk. "Come sit," he said to the Hunkpapa chief.

Chief Sitting Bull, with his hat in his hand, walked instead to the end chair closest to the widow and seated himself as he glanced curiously at the new telephone on McLaughlin's desk. Louis and Anson sat in the other chairs to the left of Sitting Bull. When we have meetings, thought McLaughlin, we are to sit in rows, in chairs. Never in circles. The circle is a baneful, pagan symbol. The Sioux perform all their rites in a circle, including that confounded new Ghost Dance.

|

Stenographer Fry titled the top of his notepad with the date and location: 25 October, 1890. Office of Major James McLaughlin, Standing Rock Agency.

"Cigar, Bull?" asked McLaughlin as he extended his cigar box to the old chief. James never called Sitting Bull "Chief", and never referred to him as chief. This was part of his attempt to diminish Sitting Bull's influence on the Sioux. Furthermore, in 1883, Senator Logan scathingly denied his chieftainship. McLaughlin also sought to undercut Sitting Bull's influence by dealing more and more with the Indian leaders John Grass for matters involving the Blackfoot Sioux and Gall for the Hunkpapas.

Sitting Bull nodded as McLaughlin expected. McLaughlin handed Sitting Bull a Virginian cigar and then held a lit match to light it. McLaughlin was always pleased to see Sitting Bull accept anything from him. It took years for Sitting Bull to concede to move out of a tipi and move into his present cabin along the Grand River. And after resisting for so long, to accept rations and schooling for his children on the Standing Rock Reservation. He was gradually understanding that it was in the red man's best interest to adapt to the lifestyle of the white man. Well, maybe not understanding, but gradually conceding nevertheless. But Sitting Bull never was one to move fast. A stubborn, proud man who could not accept the inevitable, but loved the limelight from both the red and white man.

McLaughlin thought back six years ago when he took Sitting Bull to St. Paul, Minnesota. 1884. It was only eight years after Custer. Showed him a bank. McLaughlin remembered the wheezy little banker, pale and pudgy. "Major McLaughlin and Mr. Sitting Bull, step this way, please." The vault door opened on hinges big as your fist. In the vault the banker showed him sacks of gold. Sitting Bull? He yawned. "Thousands of dollars in cash," I said, "and more in securities and bonds." Louis Primeau took great pains to explain, but Sitting Bull did not appear to grasp the concept. I gave my little speech. Told him that when the Sioux accepted their allotments in severalty they would receive a generous amount of money from the government, which they could use to buy seed, stock, tools, and the like. The banker stood there staring at Sitting Bull's bowed legs, his quilled moccasins, his greasy Pendleton robe and black stovepipe hat. If I had told him, I reckon he'd have jumped out of his socks: The eagle feather in the band of that hat, its tip had been dipped in the blood of a Ree chief. Later, as we toured the city, a fine mist hung in the air. I pointed out a Catholic church, a hardware store, a lumberyard, a power station. Sitting Bull smoked his pipe and looked around. He turned to Primeau and spoke. "He finds this a strange way for people to live," Primeau said. "Even the hornet doesn't build so crowded a nest." Sitting Bull had gone on, his cadence slow and thoughtful. 'The Hunkpapas will never live his way -- the Little Yanktons, maybe, for they are easily led. But the Hunkpapas -- never. Not in your lifetime, White Hair, and not in the lifetime of your son, or your son's son." Well, now six years later, Indian Agent Major McLaughlin thought with pride, treaties have been signed and the Hunkpapas and the other two bands of Sioux, Yanktonais and Sihasapas, are conforming on the Standing Rock Reservation -- all done without the help or approval of "The Generalissimo of the Sioux", Sitting Bull.

No. & So. Dakota were admitted to the Union in 1889. The reservation still exists today. |

"I reckon you will pick up your rations today while you're at the agency?" McLaughlin asked Sitting Bull who seemed to be enjoying his cigar.

"I must," said Sitting Bull, "my wives and children are hungry. The summer was short and the crops gave forth little." Sitting Bull had prophesied last spring the hot summer winds that had destroyed many crops.

Sitting Bull had no gift of prophecy, thought McLaughlin, but it was the act of prophecy that made Sitting Bull more of a medicine man than a chief. Regardless, his people revered the chief for it. And true, the drought had taken its toll, but the amount of Bull's efforts to learn the craft of farming would fill a teaspoon.

"In the spring, with more planning, more planting, and more rain, your crops will yield a bounty, Bull."

Sitting Bull was silent for a moment, then said, "I hope I will see what you say is true."

McLaughlin took the statement as Bull's usual challenge to his honesty. McLaughlin as an Indian Agent was respected by most all other Indians for his honesty -- he had never lied to the Indians. However, Sitting Bull had said that all white men had lied and continue to lie, and the only truth they ever told was when they promised to take the Indian's land away from them -- to that, Sitting Bull said, they kept their promise.

McLaughlin said, "You know that I speak the truth, Bull. We may not always agree, but you know I never break a promise." Then he smiled and said with a wink, "But I hope you will not consider my hope for good weather as a promise."

Sitting Bull puffed on his cigar. Then he said with all seriousness, "The meadowlarks in the field have spoken to me. They have warned me about the future, but it doesn't concern your untruths."

There he goes again with his confounded prophecies! Isn't there enough mystic hogwash about the near future being passed around? "What was the warning about, Bull?"

Sitting Bull said nothing.

McLaughlin shuffled in his chair. It's time to get to the agenda. First, he would attempt once again to make some type of impression on him with a modern new device. He wanted to keep emphasizing the benefits of civilized living. Then, he would address the Ghost Dances.

looking southeast, toward the Missouri River. Fort Yates adjoined the agency (extreme right). |

"See this black contraption, Bull. It's called a telephone." McLaughlin pushed the phone to the middle of the desk. "With it you can speak to people far away."

Sitting Bull looked on with mild interest. McLaughlin picked up the earphone and by speaking into the mouthpiece, asked the operator to ring up Mrs. Parkin, a mixed blood living at Cannonball River, twenty-five miles up the Missouri. When Mrs. Parkin was on the line, McLaughlin handed Sitting Bull the earphone and motioned him to speak into the mouthpiece.

"Hallo! Hallo!" he bellowed. "You betcha! You betcha!" That about exhausted Sitting Bull's store of English. He had spoken in the white man's tongue because he figured it was all the machine would understand.

Then as planned, the voice came cutting through the hum and crackle; a woman's voice, coming through the wire into his ear.

Sitting Bull jerked the earpiece away as if shocked. He looked at the earpiece as if it had teeth. He then quickly turned in his chair to make sure this woman was not indeed behind him. McLaughlin smiled as he saw the chief's mouth agape for the first time ever. Sitting Bull slowly brought the earpiece back to his ear, removed it once more, then back to the ear again. While he listened to the distant voice speak on, he began to regain his composure, but his eyes darted back and forth as he looked at McLaughlin. The voice was talking to him in Lakota -- Sioux.

Sitting Bull said not a word and sat listening until Mrs. Parkin had hung up. He handed the earpiece to McLaughlin.

"Well, what do you think of the telephone?"

Sitting Bull took several long puffs of his cigar and then spoke. "He says it was made by a woman," Primeau said.

"By a woman?" McLaughlin exclaimed. "Why do you say that?"

Sitting Bull sneered slightly as he explained, "With that, women can be very happy. Women now can speak from sunrise to sundown without us men being able to reach out and hold their tongue." Sitting Bull rapidly tapped his thumb and fingers together in the air as he made his point.

The room erupted with laughter. Even though Sitting Bull had smugly poohed the use of the new device, McLaughlin knew that he had been impressed with its performance. McLaughlin quickly moved on to his main concern.

"Bull, the Ghost Dances must stop! Your people are neglecting their homes and their property. There will be great suffering. They are likely to commit violence. The soldiers will come, and you will be to blame for it."

Sitting Bull said nothing. He pressed his cigar hard into the ashtray on the desk, snuffing out the last of the glowing embers.

He must listen to me. The Ghost Dances have been going on too long and are reaching a fever pitch! All started last year because a Paiute holy man in Nevada named Wovaka had a vision during an eclipse of the sun in which he saw the second coming of Christ. A new Indian Messiah had come to liberate them, was the rumor which spread quickly through the Indian camps across the country. Then, a disciple named Kicking Bear had brought the doctrine to Standing Rock and Sitting Bull this past summer. Dance and the new Indian millennium will arrive in the spring. Dance and the earth will be destroyed. Dance and Indian believers will be lifted above the cataclysm and be reunited with their dead ancestors. Dance and the earth will be filled with herds of buffalo and ponies again and the red man will eat and drink, hunt and rejoice. The new religion was being called the Ghost Dance by white people because of its precepts of resurrection and reunion with the dead.

McLaughlin understood the Sioux in Standing Rock were embracing the new religion with exhilaration. Some dances would continue for days until the participants "died", falling to the ground, rolling around and experiencing visions of a new land of hope and freedom from white people which was promised by the messiah. The dance often produced mass hypnosis in its transfixed participants. Curious onlookers were prohibited, and this was furthering the sense of mystery about the ritual. This was alarming the nearby settlers, alarming Washington, and alarming McLaughlin. A new Indian uprising was feared. McLaughlin was pressured to stop the dances. On October 15, McLaughlin had his police remove Kicking Bear from the reservation. But the dancing continued with increased fervor -- under Sitting Bull's oversight. Standing Rock's people were abandoning their cabins and pitching tipis on the flat north of Sitting Bull's cluster of cabins. Attendance at the new government school shrank from ninety to three this past week as parents withdrew their children so they could go to "church". He must listen to me.

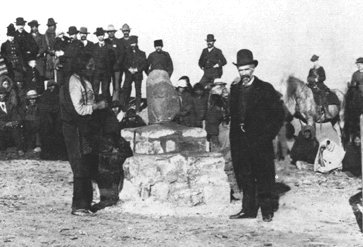

and Major James McLaughlin (R) at 1886 dedication of Standing Rock Agency. Standing Rock is named for a rock shaped like a woman with a child on her back. |

"Bull, I have done many things for you and your people," McLaughlin went on. "I told the army to let you go from Fort Randall. I got you plenty of horses and cows. I let you go with Cody." McLaughlin continued on in the Indian manner, and reviewed all the favors he had done.

"And after all of this, you repay me by disobeying my orders and leading your people astray with this Ghost Dance, this absurd story of an Indian Christ."

Sitting Bull replied, "It is not absurd. It is the truth. Christ has come back to the Indians. He came already to the whites and you nailed him to a tree -- even the Black Robes admit it. The dancing is a good thing and I believe in it."

"No," McLaughlin challenged, "one look in your eyes tells me you do not believe." McLaughlin was unsure whether Sitting Bull was a true believer in the Dance or not, but he had heard from his sources that Sitting Bull never danced himself and never directed the dances, leaving that to Bull Ghost, his dance director. Sitting Bull had also hinted at skepticism to Mary Collins, the Congregationalist mission worker who had won Sitting Bull's respect by ministering to one of his children when gravely ill.

On the other hand, from a tipi next to the dance circle, Sitting Bull presided over the community of believers and officiated as the chief apostle of the religion at Standing Rock. He encouraged his people to dance and interpreted the revelations of those who had "died" and visited the spirit land. And doggedly, at considerable personal risk, he had so far defied all efforts by McLaughlin, missionaries and schoolteachers, and by unbelieving fellow tribesmen, to persuade or compel him to cast off the religion and send the people home.

McLaughlin believed that Sitting Bull's involvement in the Ghost Dance afforded Sitting Bull an opportunity to revive his authority and influence, which McLaughlin so strongly wanted to curtail. Instead of the Dance rekindling Sitting Bull's authority, McLaughlin hoped that that Sitting Bull would use whatever authority he had to stop the dancing of the people. However, regardless of Sitting Bull's stature in the community, this Ghost Dancing must stop!

Sitting Bull raised his hand. "Sometimes White Hair's advise is good, but not today. Being a white man, you do not understand the Dance." He flashed his teeth and said, "We will go together, you and I, to beyond the yellow faces west of the Utes, where this Dance began. Together we will find the Messiah. If we do not find him and all the dead Indians coming his way, I will return to my people and tell them it's a lie. If we do find the Messiah and the ghosts, you will let the Dance go on."

There it was: a chance! It was conceivable the Bureau would let us go, thought McLaughlin. Two, three days out, dig up this Paiute phony, let them burn a little tobacco, search the skies for buffalo and horses and dead Indians, then cart him back, and if he still spouts this nonsense, throw him in the guardhouse. No, wait! The whole idea of the quest was childish and absurd!

"No," McLaughlin said. "It would be as futile as trying to catch up with the wind that blew last year."

Sitting Bull stood from his chair. "The Ghost Dance does no one any harm. It threatens no one. The whites have their religion, we have ours, neither should interfere with the other." Sitting Bull turned and walked to the door. He stopped and turned to McLaughlin and said, "Besides, the passions of the Ghost Dance are not easily cooled. The flames burn too fiercely even for me to put out."

"We will dance," the old chief continued, "We will dance and come spring will be the New Millennium for the Indian." Sitting Bull walked briskly from the room.

Primeau and Fry looked anxiously at McLaughlin. McLaughlin walked to the window. "Come spring, gentlemen," McLaughlin said with a sigh, "it is also being said that the earth would be covered with new soil."

McLaughlin looked out the window at the old chief atop his horse. "Soil which would bury all white men."