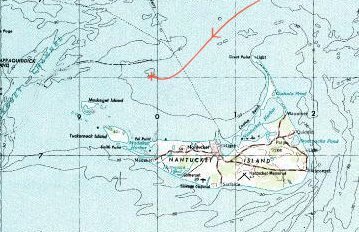

Aground near Nantucket, Massachusetts 17 December 1851 |

17 December 1851 - 6 p.m.

Patrick McLaughlin gasped as he felt cold seawater seeping up from below him. Cold, weakened by hunger, and trembling at the thought of water entering the ship, he tried to clear his head. Could this water have entered from above? No, the hatches had been battened down securely as the ship had entered the storm. Patrick's instincts told him they were in serious trouble.

Patrick clambered upwards in an attempt to stand on his feet. In the complete darkness of the rocking ship he hit the back of his neck hard against someone's legs above him and fell forward to his knees. As he slowly tried again to get on his feet, Patrick realized that because the ship was increasingly tilting to starboard, the floor of the hold could no longer be considered "down" anymore. Getting around in their world below deck of the stricken British Queen, required walking while using one's arms and knees to brace themselves, or simply crawling across side bunk boards.

On his feet, Patrick held on securely to a bunk post as the ship was rocked and slammed by the wind and waves. He told himself he must try to sound calm. "Th-the ship is takin' on water," Patrick announced to the emigrants huddled in the blackness around him.

"Wha-what?" "Feel along the bottom here! "Oh dear God, we're sinking!" came the mixed cries of disbelief, confirmation, and panic which flowed up and down the long row of the 200 passengers in steerage.

"I think we hit something," offered George Devlin who's booming voice was overheard over the outcry. "It's opened us up!"

Rectangle is area of detail shown in map below. |

"An iceberg?" wondered Richard Browne. This brought gasps and murmurs.

"A rock, I'd wager," suggested John Strahan. "A bunch of rocks. And we're a sittin' right on top o' them! Will ya listen to the grindin' below?"

Many of the emigrants agreed with John. After a huge wave would rock the ship back to port momentarily, she would then fall back down hard, with a jolt and booming thud and crackling noises.

"Won't you quiet down, woman?" William Bennett roared at Margaret, his howling, blubbering wife. "If the ship is sitting on rocks, we can't very well sink now, can we?"

"We should tell the captain," said George Devlin. "James Clarke! 'Tis best you inform the captain we're takin' on water down here!"

James Clarke was the spokesman for the passengers in steerage. At age fifty, and with his wife and four children aboard, he had been designated by Captain Connay to communicate to the captain any concerns or events regarding the passengers.

"On my way," said James Clarke. Clarke wove his way with care through the darkness and emigrants to the forward hatch where he would try to alert the captain by pounding on the hatch door.

Above deck, the storm continued to grow in intensity. The wind was blowing steadily at fifty knots from the north, creating twenty and thirty foot waves which crashed down upon the stricken British Queen. The bow was pointing north as she lay helplessly aground on the sandbar. With the ebbing tide, the ship was listing heavily to starboard. Masts, deck, and hull were all taking a terrific beating from the wind and waves. The shrouds and stays were tight as fiddle strings as the wind howled over the rigging, sending loose ends of ropes snaking through the air. Every plank on the boat was being subjected to the tremendous pressure of the waves battering the ship by sitting on the seabed. If they had not run aground, this pressure would be shrugged off or cushioned by being afloat in the water. Captain Connay knew that since they could not move off the sand, eventually the ship would be broken to pieces. The longer they were in the fury of the storm, the sooner this would happen.

ran aground NW of Nantucket Island. |

Captain Connay could not be sure just how many miles separated them from land, and in what exact direction. According to his charts, he believed they were somewhere northwest of Nantucket Island, Massachusetts. The winds had blown the ship off course and into this dangerous spot. Now, the blowing snow and spray still kept the visibility close to zero; he could not see the tops of the masts nor the bow of his boat from the forecastle. They had no means of sending a signal, no emergency flares. The lifeboats were no option; besides having no means of navigating towards land in the storm, they would certainly swamp immediately after launching. Their best chance of rescue lay in being seen by a passing vessel but, as he knew, most shipping steered a wide berth around this dangerous spot.

Connay called out to his crew to set their distress signal. The red duster, their flag of the British merchant fleet, was turned upside down on the mizzen mast. The flag could barely be seen from deck through the blowing snow. Grimly, Connay set a couple lookouts on deck. His first mate Tibbits approached from the bow.

"Clarke wants to talk to you," Tibbits hollered to Connay as another huge wave broke across the stern. "He'll be below the forward hatch."

Connay nodded and they slowly made their way along the starboard bulwarks. "Make sure the men are wearing lifelines on deck at all times. We both should be wearing them also," ordered Connay. "Grab a lantern out of the forecastle cabin," Connay told Tibbits. The ropes holding the batten over the hatch were loose and the captain pulled up the hatch door against the gale and climbed below.

Patrick could see the shadowy figure of someone climbing down the ladder into the hold. Shortly after, another figure followed -- the hatch door slamming down hard above them. A match flared and sizzled out. A curse, and another was lit, which in turn lit a lantern that illuminated the wet, puffy face of Tibbits who looked at the emigrants before him with disdain. Due to the chance of fire, matches and lanterns were never to be lit below deck unless for special purposes authorized by the captain. Tibbits handed the lantern to the captain.

|

"Captain Connay has come below!" whispered someone in back of Patrick. The captain hadn't ever been seen below deck during their eight week voyage. The emigrant's eyes were almost blinded by Connay and Tibbits, who were wearing bright yellow oilskins in the light of the brilliant lantern.

Captain Connay held the lantern out in front of him as he slowly surveyed his frightened cargo. His wet, round face was expressionless as he gazed wide eyed from person to person, item to item -- glancing here and there, left and right.

James Clarke broke the silence by saying, "Captain, there's water comin' in from below."

Connay and Tibbits looked down at the seawater now several inches deep, running along and into the bottom bunks and making small splashes with the rocking of the ship.

Captain Connay straightened and cleared his throat. "We have run aground off Massachusetts," he said with a loud, firm voice. "Chances are, we will be rescued by a passing ship. Until then, you will attempt to keep yourselves warm and dry here below. Believe me, you are better here than above deck. As you know, we have no food left. I'll have your rations of drinking water sent down soon." Connay turned to Tibbits. "Find out what you can about the condition of the hull below and report back to me." Connay turned and climbed back up to the top deck.

Tibbits made his way through the emigrants, one hand holding the lantern and steadying himself, the other holding his handkerchief over his nose and mouth. After a few minutes below of inspecting the lower depths of the ship, he returned very disturbed. Hurriedly, Tibbits kicked at the emigrants on the floor and screamed under his handkerchief, "We're doomed to be sure! This ship will be beaten to smithereens by dawn! We'll be floating fish bait!"

Upon hearing this, the emigrants let out great cries of despair.

"Shut your gob, you ugly wench!" Tibbits barked as he swung his lantern threateningly close to Margaret Bennett's head who was wailing loudly. The ship lurched and Tibbits' lantern shattered into pieces against an upper bunk, setting a blanket and straw on fire. Tibbits knelt and frantically attempted to beat the fire out with his hands. As the fire spread, Tibbits screamed, "Someone, quick! Throw some water on this!" Tibbits now pounded at the smoky blaze with his oilskin hat.

Patrick reached down for a wet blanket, but James Andrews was quicker. Without hesitation, James picked up the large, full bucket and threw its contents upon the fire and Tibbits with one smooth motion. The fire was instantly extinguished and complete darkness engulfed them once again. Coughing, dripping wet, and sputtering, Tibbits calmed down considerably, as did the frightened emigrants. It was a close call. An out-of-control fire could run rampage through the old timbers of the British Queen in minutes.

Lighting a match and dripping from under his hat, Tibbits made his wobbly way to the ladder leading to the top deck. "There won't be a word told to anyone about what happened," he threatened the emigrants, some of whom were trying their best not to smile or snicker. Tibbits sniffed at the powerful new odor about him. He lit another match and looked down at himself, then looked over at James Andrews who was still holding the bucket.

"Wh-why, y-you..." the red-faced Tibbits snarled at James -- the match burned his finger and went out. Seething with anger, Tibbits raced up the ladder and into the storm above, cursing all the way and smelling very much like their potty bucket.

The emigrants' laughter about Tibbit's christening did not last long, as the news of their plight was spread all the way back to the rear of the hold. The emigrants -- some being sick, most being famished -- were all cold and frightened. As the rocking ship threw them about, they put on all the dry clothing they had and huddled together, trying to avoid the icy seawater intruding into their home.

17 December - 11 p.m.

The fury of the storm continued. The lookouts on deck could see nothing through the snow but twenty and thirty foot waves pounding down on them. Occasionally, the waves carried large chunks of ice which pummeled the planking and masts. The temperature dropped well below freezing which was turning the slush on deck to ice.

Below deck, the encroaching icy seawater was now several feet deep around the emigrants. Their possessions were all under water below them as they were crammed into the highest bunks. In addition, they were now getting wet from new leaks above them.

18 December - 7 a.m.

was buffeted by 20 - 40 foot waves. |

As dawn broke, the storm was blowing as strong as ever, although the snow was easing. Huge waves continued to batter and twist the ship. Disappointingly, in the dawn's gray light, Captain Connay and his lookouts could see no sign of land or ships in any direction. Their prospects seemed bleak.

A young crewman was washed overboard as he was cutting away rigging from the bowsprit. Luckily, he was wearing a lifeline from which he dangled close to the churning waves for over five frantic minutes. The crew finally succeeded in hooking the swinging sailor and hauling him back on deck.

Below deck, six feet of water was now lapping at the passenger's feet. Cold, sick, and miserable, the terrified band huddled together, seeking comfort as much as warmth.

18 December - 8 a.m.

Twelve miles away on Nantucket Island, perched in the south tower of the Unitarian Church on Orange Street, old Martin Adams scanned the island around him for fires. Adams, a retired captain of a whaling boat, was on fire watch duty every morning. Five years ago, without lookouts, Nantucket Harbor had been completely destroyed by fire. Nantucket's waterfront was now lined with empty wharves and abandoned warehouses. These days, the sea-loving people of Nantucket were without a lot of opportunities to earn a living and the talented resident ship pilots with their crews and families struggled to keep their community going. Salvaging shipwrecks along the New England coast was a lucrative business for mariners with skills and nerve.

Winter had set in early in Nantucket this year and for days the howling winds had forced ice floes into the Sound. Adams was 120 feet above the harbor in the tower which was being shaken by the strong winds. Visibility on a good day was 20 miles, but with today's blowing snow it was just enough that Adams could see through his long-glass a large three-masted barque to the northwest and noticed that its flag was flying upside down.

"Ship in distress!" cried Adams and he hurriedly passed the word to the men in the harbor.

18 December - 9 a.m.

Another mountainous wave -- this one forty feet high slammed down on the stricken ship, burying it under tons of water. Above the thunderous pounding was a loud crack like a rifle shot as the foremast broke. It came crashing down across the deck. The wind and waves pushed the mast in all directions, scraping and prying at the decking and bulwarks. The decking planks in the bow and stern were loose. A wild cry arose from the crew, loud enough to be heard even above the storm. "The seams! The waves have forced open the deck seams!"

The next moment, a wave of icy sea water poured down onto the sick and frightened emigrants below, drenching them from head to foot including the last of their dry blankets.

Connay ordered the foremast to be chopped away to prevent the British Queen from tearing herself apart. The top of the mizzen mast had also broken clean off and was tangled in the lower rigging. Quickly, Connay had their distress signal salvaged from it and had the upside-down flag run up to the top of the main mast.

18 December - 10 a.m.

While the crew struggled to chop away the foremast, the rest of the mizzen mast also broke under a huge thirty foot wave. It fell towards the stern where it pinned and broke the arm and ribs of the second mate. The crew worked furiously to chop loose both masts thrashing the ship.

18 December - 11 a.m.

The storm blew on. The two masts had been chopped away; the loss of the weight of the masts had righted the ship somewhat. Captain Connay started to have his fragile passengers brought up to the top deck. There was eleven feet of water in steerage now. Their only chance for survival was to wait in the weather until being rescued. If the storm continued, the weather would start taking its toll, with the inevitable breaking up of the ship finally putting an end to their hopes.

Below deck, everyone helped the sick and the weakest exit out of steerage top deck first. Then, women and children would go next. The pathway to the hatch door was planks a couple feet wide laid across the upper bunks.

18 December - Noon

At Nantucket, the islanders had put together an initial rescue plan and preparations were underway. Everyone on the island was aware of the British Queen's precarious situation, and primed to act as soon as the storm subsided somewhat. The islanders strained to see through the snowy shroud with their telescope in the church tower. They were alarmed that now there appeared to be masses of passengers gathering on the main deck. But the gales and the tides rendered any immediate rescue impossible.

18 December - 3 p.m.

Over two hundred passengers hunkered together on the open main deck of the British Queen in the freezing winds and the occasional waves which threatened to wash them overboard. Soaked to the skin, the emigrants huddled under their wet blankets seeking any possibility of warmth and comfort. Those who were the weakest were given shelter from the waves under the lifeboats.

With the approaching darkness, Captain Connay realized that there was no chance of a possible rescue until the following day, assuming that they managed to survive that long.

18 December - 11 p.m.

The passengers had been huddling on deck now for twelve hours. Patrick could not stop his violent shivering. He curled up into a ball with people shivering all around him, as they prayed for someone to take them away from this living nightmare -- or prayed for, at the very least, a warm sunrise.

19 December - 6 a.m.

The winds and waves were still very strong out of the north. The snow had tapered off. But there was no warm sun. Patrick was weak and shivering less. His hands and feet were numb. Patrick prayed for a miracle.

19 December - 8 a.m.

Gazing through their long-glass from the church tower, the residents of Nantucket were relieved to see that the wreck had survived pretty much intact overnight. They prayed for the welfare of the passengers huddled on deck -- that they would survive until they could reach them.

19 December - Noon

It was high tide. It was time to move -- even with the northerly gale still persisting. Dozens of island volunteers sprung into action to implement their plan. A paddle-steamer which maintained a regular ferry service to the mainland, the Telegraph, would tow the schooners, Hamilton and Game Cock, over the sand bars and up to the mouth of the harbor, where they could raise sail. On duty on the Telegraph, as she built up steam in the harbor, were Captain George Russell and a professional wreck master, Captain Thomas Gardner. The schooners were commanded by the Patterson brothers, William on the smaller Game Cock and David on the Hamilton. David declined the tow at the last minute and the Hamilton carefully made its own way out to the wreck.

Out over the sand bars the aptly named Game Cock cast off her tow, set her storm sails, and plunged through the wind and waves. The Telegraph followed at a more sedate pace. She needed at least an eight foot draft, and would stand off some way from the wreck, as the ice could damage her paddle wheels. The passengers, if successfully transferred to the schooners, would then be transferred to the Telegraph for the trip back to the harbor.

19 December - 1 p.m.

|

"Sails ho!" yelled the lookout excitedly over the roar of the gale as the ships were sighted. "All hands, hoy!" ordered Captain Connay to his crew. Three ships were heading towards them. The frigid mass of emigrants slowly stirred as they realized that help was on its way and the news warmed and gladdened their hearts. This was the first indication in more than 36 hours that they might be saved and their prayers had been answered. Patrick and others clamored against the bulwarks to get a glimpse of their rescuers.

Anchoring as close to the British Queen as they dared, Nantucket's expert mariners conferred. They combined some crews, and using a small boat, rowed across through the raging sea to the stranded ship. Captains David Patterson and Gardner then climbed aboard the British Queen.

Captain Connay informed them, "We have no cargo and the ship is a total loss, it is not insured. All I want is to get my passengers to safety. The water has been up over the lower decks all night and they are in a horrid condition."

The rescuers signaled the Game Cock to lay alongside the wreck. Carefully, the Game Cock approached the British Queen's bow, dropped an anchor, and payed out her anchor cable until she lay across her bow, then slowly worked down her starboard side.

by Rodney Charman - Maritime Artist. |

Clinging to the wreck with mooring lines, the Game Cock was heaving high above the British Queen with each rising wave, then seconds later smashing down on the sandy shoal. Captain Connay ordered that women and children and the sick would leave first.

One at a time, a loop of stout rope was drawn tight around each departing passenger under their arms and around the chest, with the other end of the rope in the strong hands aboard the schooner. As a wave would bring the level of the schooner up fairly close, the passenger was to jump across into piles of blankets and the waiting arms of the rescuers on the Game Cock. It was a dangerous operation. Besides a possible long bone-crushing fall, one slip or mistiming and they could be crushed between ships.

One-by-one the passengers jumped to safety where they were hustled below and wrapped in blankets. Patrick watched as Maria Maguire jumped late and slammed against the side of the schooner riding on a high wave. Fortunately, she was jolted over the rail by her lifeline an instant before being crushed. When some 60 passengers were aboard the Game Cock she started striking the bottom hard. As the tide was turning, there was no time to transfer the survivors to the paddle steamer. Instead, the Game Cock headed back to the harbor.

The Hamilton eased in alongside the wreck and the rescue continued. As the passengers waited for their turn to abandon ship, sprays of icy seawater pelted their exposed flesh.

Illustration from The Famine Ships by Edward Laxton. |

It was found that Abraham Thompson, age 45, who had been fighting the fever, did not survive the long night in the weather. Shortly after, they also found that Christopher Nevin, a 35-year-old wheelwright, had died from the exposure. Their bodies were passed to the Hamilton.

Patrick and his friend James were among the last to leave the wreck before the crew. After Patrick's jump onto the pile of blankets, he was helped below out of the wind, where his frostbitten hands and feet slowly and painfully thawed under two large blankets. As the day darkened and the tide turned, every one of the passengers and crew was rescued without the loss of a single person.

Captain Connay, with the British Queen's logs and ledgers tucked under his belt, was the last to leave her broken decks.

19 December - 5 p.m.

The Telegraph and Hamilton reached Straight Wharf in Nantucket Harbor where the Game Cock was already tied up, and a large crowd waited in the cold and dark to take charge of the emigrants. The survivors were taken to a variety of fire houses, church halls, or private homes where they would spend six days recovering from their dreadful ordeal.

21 December 1851

The remains of the wreckage of British Queen was sold as she lay for $290 -- worth so little, but she did the job of keeping over 200 clinging emigrants above water for two days. There was very little left to salvage after the storm subsided.

25 December 1851

On Christmas Day, Patrick and the more than 200 Irish emigrants went aboard the old paddle steamer, the Telegraph, and set out for New York to complete their journey to their new world.

However, two of the survivors, newlyweds Robert and Julia Mooney, stayed on Nantucket Island, happy to stay among people who had made them so welcome, and who had risked their own lives to bring them ashore.

The people of Nantucket were truly heroes. By risking their own lives against the angry demands of the sea to help those in distress, they embraced the motto they live by as lifesavers: You have to go out, but you don't have to come back.

Standing at the bow of the Telegraph, with full stomachs and freshly shaven faces that hadn't seen a razor in two months, Patrick McLaughlin and James Andrews basked in the warm sun. Despite wearing tattered clothes and losing their few, treasured possessions, all survivors aboard the Telegraph were in a grand mood. The Irish children played on deck with their new model ships made out of whale bone, reenacting their rescue. The gals primped and preened their long hair in the sun. Patrick and James hardly recognized them. The men from Limerick joked among themselves with new rhymes about Nantucket. Fathers spoke excitedly about their dreams of farms in places named Vermont, or Pennsylvania, or Ohio.

"Patrick, I believe there's grey hairs sprouting on your young noggin," observed James with a smile. "Been worried lately?" James was feeling good. His chronic cough had disappeared within the last week. James was crediting it to many bowls of what was called "clam chowder".

"Naw, it runs in my family," chuckled Patrick. "'Though we'll have quite a story to tell our children and grandchildren some day, won't we?"

They gazed ahead at Long Island, New York in the distance.

"If it weren't for the heroes of Nantucket, there wouldn't be children and grandchildren... nor that 'some day' you're talkin' about," James murmured gratefully. He threw a big chunk of his bread to a seagull overhead.

How true, Patrick thought. How special each day is! "Every day here in America is as good as Christmas day in Ireland," the Irish fellow in Wisconsin had written. How very true! Smiling, Patrick leaned back in the warm sun in his tattered coat. His coat's pockets contained all of his worldly possessions: a small leather pouch containing a silver sixpence and seven green, triple-leafed clovers from Ireland, a piece of "Nantucket cranberry pie", and his leather-working tools.

Yet, after counting everything he really had, including the gift of "today", he felt rich.

Now, Christmas day in America is... thought Patrick, ... well, 'tis grand!

Grant's Notes & Resources:

This is a true story. It is a dramatization, told with passenger Patrick McLaughlin as the main character, of the actual voyage of the British Queen. All "coffin ship" voyages from Ireland to America during and after the Irish "Great Famine" were difficult voyages -- the British Queen's was especially so, with its long duration, storm, and shipwreck.

I learned of this story by finding Patrick McLaughlin as a passenger on a ship named British Queen at the Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild.

( http://istg.rootsweb.com )

Thus, my first reference for this story can be found at the British Queen's passenger list at:

http://istg.rootsweb.com/v2/1800v2/britishqueen18511000.html

Passenger #9 is Patrick McLaughlin - male - 22 - shoemaker.

With what we know about our Patrick at the present time, and from these scant entries in the passenger list, this Patrick may or may not be our ancestor. I suggest it is plausible that this Patrick is our ancestor. There are factors which add or subtract from the plausibility. By comparing what we know and presume about our ancestor to the passenger list entries makes for interesting speculation:

| + plausibility | - plausibility |

|---|---|

| Our Patrick worked with leather in 1857 as a tanner and currier. | There is an age conflict. Our Patrick was 23 in late 1851. |

| Several of our Patrick's children worked with leather as a tanner, shoemaker, or shoe stitcher. | |

| Our Patrick certainly sailed by ship from Ireland to America (or Canada), bound most likely for New York. | |

| Our Patrick probably emigrated in the 1850's. The greatest percentage of famine emigrants was from 1846 - 1851. |

If our Patrick sailed at a different time, I offer the story (up to the shipwreck, that is) as a veritable example of what our Patrick most likely endured aboard a coffin ship.

|

|

Note: The captain of the British Queen was listed on the manifest for Nantucket as Connay, but according to Laxton's work, his name was Conway.

--Grant