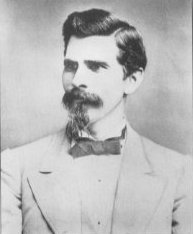

in 1876 - As Indian agent at Devils Lake Agency before coming to Standing Rock Agency. |

Major James McLaughlin shuffled through the new mail in the light of the lamp on this late autumn afternoon. It had been a chilly day this October 25 in 1890. Cold northerly winds were blowing against the agency's windows. Could be snow coming, thought McLaughlin. He thought of the Indians, who, after 9 years of progress, were now living in log or frame houses on Standing Rock Reservation. Warm houses -- most with reconditioned wood-burning pot belly stoves that McLaughlin bought from the railroad. McLaughlin had encouraged log cabins since he arrived in 1881, but some still built tipis for summer use. When Sitting Bull and his band were released from imprisonment at Fort Randall in May of 1883, they had pitched their tipis just south of Fort Yates, within eyesight of McLaughlin's office. A year later, they too had moved down to Grand River and erected log cabins -- much to McLaughlin's satisfaction.

|

McLaughlin wondered how well the two new large stoves were working up north in the Cannonball Day School. He had built that school in '84, and, until the recent distraction with the confounded Ghost Dance, had served 60 children. James made a mental note to make a visit there tomorrow. The reservation had two other schools; a boarding school staffed by priests and sisters that opened in 1881 with 77 students, and an industrial farm school 15 miles south of the agency that was operated by the Benedictines. Even the defiant Sitting Bull had finally consented to sending several of his children of his two wives to school.

The Indian people of Standing Rock were trying to adapt to a totally new way of life and much progress had been made over the last decade. Although some Indians had some success in agriculture, most were dependent now on rations, wage labor, and hunting due to grasshoppers, drought, and poor soil. Because there was little game left on the reservation, McLaughlin worked with the cooperative chiefs John Grass, Two Bears, and Gall to strive for success with their crops. Wagons and cattle were issued to Indian men. A recent sign of Indian acceptance was their purchase of two mowing machines.

|

|

However, the Standing Rock Sioux were not willing to give up all their traditional customs. The traditional form of marriage by gift exchange continued, although McLaughlin, being Roman Catholic, regarded it as a good sign that no couples lived together without some type of ceremony. McLaughlin was bewildered by the apparent contradiction between the adoption of White-style clothing and short hair -- signs he took for assimilation, and the continuation of Indian dances. In the early '80s, McLaughlin blamed the dances for neglect of crops, desire to travel, poor health, and impoverishment. He finally prohibited all dances except the grass dances which he allowed to be held only on Saturday afternoons. And now, McLaughlin groaned, they're dancing again day and night -- endorsed and fueled by Sitting Bull, his old antagonist whom McLaughlin had tried so hard to win over. Seemingly always at odds, but with respect for each other, the two men coexisted in relative harmony. But after this afternoon's showdown with Sitting Bull regarding the Ghost Dance, their strained relationship had become one of discord.

Sitting Bull: A great leader to some -- a thorn to others.

Sitting Bull was considered by McLaughlin and those in government as "an obstructionist, a foe to progress." After orchestrating such Sioux battles as Little Bighorn, which demolished Custer and the seventh cavalry in 1876, he and his band fled to Canada. After almost starving, they returned to spend prison time at Fort Randall. After his release, Sitting Bull continued to resist all the government's attempts to civilize the Sioux. Most of the Sioux looked to him as a leader with a vision: The great hope and purpose of his life was to unify the tribes and bands of the Sioux and hold the remaining lands of his people as a sacred inheritance for their children. He never signed a treaty to sell any portion of his people's inheritance, and he refused to acknowledge the right of other Indians to sell his undivided share of the tribal lands.

McLaughlin recalled his first meeting with Sitting Bull, soon after Bull was released from Fort Randall to live at Standing Rock. Sitting Bull informed McLaughlin his people considered he himself as their leader and he alone knew what is best for his people's future. Among other requests, Sitting Bull asked that all rations be given to him for distribution.

McLaughlin had quickly cut him off. "Do you want to know how you can best help your people?" he asked. Sitting Bull did not reply. McLaughlin led him outside to a field where some other Indians were busy working. "Like this." He handed him a hoe and ordered him to get to work.

With rations distributed to individual families, McLaughlin was able to withhold rations from those who did not adhere to the rules and regulations of the agency. It was an effective tactic. Early on in his administration, he found he was able to attract Indian children -- Sitting Bull's children included, to school only by withholding their rations. Withholding rations of the Ghost Dancers would not nip the problem in the bud; McLaughlin felt Sitting Bull was the source of that problem at Standing Rock.

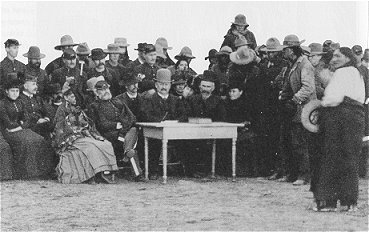

James McLaughlin is seated to the right behind the table with wife Louise at his side. See a large panarama of this scene by clicking here. (Will open up new window) |

On the Standing Rock Reservation, Sitting Bull and his band of "hostiles" apparently desired to just live quietly and to avoid trouble. But his presence was a constant reminder of Sitting Bull's opinion that the government was not treating the Indians fairly. McLaughlin tried to keep him in the background by dealing with more cooperative chiefs and by encouraging Sitting Bull to leave the reservation as often as possible. The exposure to other cultural events may be beneficial to all, hoped McLaughlin. Sitting Bull attended the opening of the North Pacific Railroad in Bismarck, accompanied the Buffalo Bill Cody shows through the eastern states as a star attraction, and visited the Crow Agency in Montana. Sitting Bull participated in Bismarck's celebration of statehood in 1889.

But when a Congressional commission arrived at Fort Yates in 1889 to obtain signatures from Indian leaders agreeing to the creation of six smaller reservations from the Diminished Great Sioux Reservation, and therefore ceding nine million acres of land to the government, McLaughlin did not invite Sitting Bull. Despite McLaughlin's attempt to avoid Sitting Bull's reaction, Sitting Bull attended anyway and voiced his displeasure with the agreement. When he was stifled by the Commission, Sitting Bull left and arrived later during the signing where he and his band of twenty mounted hostiles charged into the crowd of Indian signers and began to scatter them. McLaughlin had anticipated such a move, however, and Indian police commanded by Lieutenant Bull Head swiftly gained control and expelled the troublemakers. The agreement was then ratified. Also that year, Congress approved opening the reservation to White settlement.

McLaughlin believed the failure to prevent the reduction of the reservation and the increasingly obvious presence of White homesteaders moving into reservation lands may have encouraged Sitting Bull's participation with the Ghost Dance and contributed to his defiance of McLaughlin's pleas to stop the dancing. And McLaughlin could not ignore the chief while this dancing continued in the flat north of Sitting Bull's cabins.

"What if Sitting Bull does not listen to me?" thought McLaughlin as he opened some correspondence forwarded to the Agency by Washington. Attached to a letter of alarm by Secretary of the Interior John W. Noble was a letter signed by nearby white homesteaders. McLaughlin sighed as he read the homesteaders' letter in his hand...

Mead County

State of South Dakota SD

Sept. 26, 1890

We the undersigned settlers of eastern Mead County South Dakota, and the United States of America, Do hereby ask in humble prayer for military protection during the trouble on the opening Reservation against the Sioux Indians. Indians residing in villages along the Cheyenne River, from the forks down to Cherry Creek.

Chiefs Spotted Elk, or Big Foot Brave Eagle and Red Skirt, and their bands.

We ask in most humble prayer, and further demand that we have protection of our lives and our children's and our homes and our property.

Signed,

Elbert Jones Peter Quinn J.B. Slicks John Reynolds A.J. Culbertson J.W. Duvall P.T. Lemly Peter Dunn John Dunn

In his attached letter, Noble wrote that the matter was being taken very seriously with increased patrols in that area organized by Fort Yates commander, Lieutenant Colonel William Drum. Meade County was south of Standing Rock reservation. Now there were anxious white homesteaders both on and off the reservation -- fueled, McLaughlin believed, by the Ghost Dance. McLaughlin knew Big Foot, Brave Eagle, and Red Skirt to be among the group of Sitting Bull's "hostiles." They also were said to be among the most ardent participants in the Ghost Dance.

Downhearted, Major McLaughlin picked up his pen and composed the letter which could not wait another day.

Hon. T. J. Morgan

Commissioner of Indian Affairs

Sir:

I have the honor to state there is now considerable excitement and some disaffection among certain Indians of this agency. I trust I may not be considered an alarmist ... and do not wish to be understood as considering the present state of excitement so alarming as to apprehend any immediate uprising or serious outcome, but I do feel it my duty to report the present "craze" and nature of the excitement existing among the Sitting Bull faction of Indians over the expected Indian Millennium, the annihilation of the white man and supremacy of the Indian, which is looked for in the near future and promised by the Indian medicine men as not later than next spring, when the new grass begins to appear, and is known amongst the Sioux as the return of the ghosts....

Maj. James McLaughlin

Indian Agent, Standing Rock Agency

In the long and truly remarkable letter, McLaughlin excoriated Sitting Bull with nearly every epithet his dictionary could suggest: vain, pompous, untruthful, and cunning; abject coward, disaffected intriguer, polygamist, libertine, habitual liar, active obstructionist, and chief mischief-maker; and, in stunning contradiction to the litany of abuse, "an Indian unworthy of notice."

As "high priest and leading apostle of this latest Indian absurdity," McLaughlin declared that some time during the winter, Sitting Bull be seized and transported to a military prison distant from the Sioux country. With Sitting Bull removed, "the advancement of the Sioux will be more rapid and the interests of the Government greatly subserved thereby."

The reactions by the government to the precarious situation.

Reluctant to face the political implications of such a move, Washington officials took refuge in an evasive delaying tactic. On October 29 orders went out to Standing Rock for McLaughlin to inform Sitting Bull and his cohorts that the "honorable Secretary of the Interior" was "greatly displeased with their conduct" and would hold Sitting Bull "to a strict personal responsibility" for any trouble resulting from "his bad advice and evil councils." To demonstrate his submission to government authority, he must at once bring his influence to bear against "the medicine men who are seeking to divert the Indians from the ways of civilization."

McLaughlin shrugged grimly upon reading the almost laughable irrelevance of these instructions to the volatile situation on Grand River. He did not rush off to repeat the secretary's inanities to Sitting Bull. Rather, he again called on Bull Head of the Agency's police force to deliver the "warning." Bull Head had no love for Sitting Bull, they had clashed in the past over some trivial incident, and bad blood had bubbled ever since.

were worn by the Ghost Dancers who believed they protected them from bullets. |

As the following month proceeded, the tensions grew as the Ghost Dance went on in full swing. The Ghost Dancers were now wearing "Ghost Shirts", brightly colored shirts emblazoned with images of eagles and buffaloes. They believed the Ghost Shirts would protect them from the bluecoats' bullets. Word was out throughout the nation of a crisis on Indian reservations. Hysteria swept the white communities of Nebraska, and North and South Dakota as citizens warned of an Indian uprising and appealed for government arms and military intervention. McLaughlin received a telegram on November 14 that assigned the army "responsibility for any threatened outbreak." McLaughlin was uncertain exactly what that meant.

On November 20, troops moved suddenly to occupy the Pine Ridge and Rosebud agencies in southern South Dakota. Issuing the marching orders from his Chicago headquarters was a soldier chief well known to the Sioux, Bear Coat: Major General Nelson A. Miles. As the soldiers marched in, the Ghost Dancers took refuge on an elevated tableland in the Badlands, well watered and protected by steep cliffs and bluffs, that quickly became known as the Stronghold. There, they continued to dance while the military authorities tried to decide how to get them down without provoking a fight. A large contingent of "war correspondents" descended on the agencies and with breathless dispatches kept the nation in daily suspense.

McLaughlin and Lieutenant Colonel Drum of Fort Yates wanted no such scenes at Standing Rock. They knew that the moment a blue column marched out of Fort Yates for any purpose, the Grand River Ghost Dancers would stampede, either to unite with their kin in the Stronghold or flee to their own Stronghold. McLaughlin therefore intended that his Indian police, not soldiers, should arrest Sitting Bull.

A famous Indian scout and showman sent on a dangerous mission.

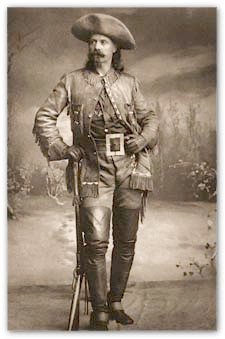

General Miles also believed that Sitting Bull should be removed, but he had his own discrete plans of how to do it successfully. On November 28 Buffalo Bill Cody, traveling showman and fresh from a European tour showed up at Major McLaughlin's door.

Sitting Bull had toured with Cody's Wild West Show briefly in 1885. The duo was billed as Foes in '76, Friends in '85. |

"What are your intentions?" asked McLaughlin incredulously.

"Upon General Miles' orders, I am to secure the person of Sitting Bull and deliver him to the nearest commanding office of U.S. troops," exclaimed Cody. Cody presented McLaughlin with one of Miles' calling cards with the order scribbled on the back for McLaughlin and Lieutenant Colonel Drum to provide such transportation and protection as Cody might request.

McLaughlin was chagrined. Buffalo Bill Cody and Sitting Bull had been friends for a season's tour, but to turn the one loose on the other in the present situation might lead to unpredictable consequences.

Fortunately for McLaughlin, Cody could not get underway that day. As McLaughlin later explained delicately, "Cody was somewhat intoxicated, he continued to drink even more, and was in no condition to attend to business that afternoon and evening."

What McLaughlin discreetly failed to mention was that he, Colonel Drum, and the Fort Yates officers conspired to ensure that Cody continued to drink. At the officers' club they worked in relays while McLaughlin frantically sought to head off what he feared would become a trip to disaster. McLaughlin immediately telegraphed a protest to Washington. Cody's mission would set off a fight, he warned the Indian Office, and should be canceled at once!

The next morning, November 29, Cody announced he would start for Sitting Bull's camp. Colonel Drum had no choice but to provide him with a wagon and team for the journey.

McLaughlin, however, had still not lost the game. He summoned his friend and agency interpreter, Louis Primeau.

"Louis," McLaughlin requested, "try to intercept Cody and delay him somehow."

"How?" inquired Primeau. "By heading him in the wrong direction?"

"Anything!" pleaded McLaughlin. "Perhaps try appealing to his thirst with a refreshment break before he continues on with his journey. No, on second thought, that may increase the chance of trouble if he reaches Sitting Bull. Just see what you can do while I wait for a response from Washington."

Primeau, on horseback, speedily circled around using other roads and approached Cody from the front. When they met, Primeau stated to Cody that Sitting Bull would not be found at his home, that even then he was headed for the agency on another road. Cody turned around, somewhat irritated. Meanwhile in Washington, Secretary Noble had hurried to see the President, who overruled Miles and rescinded Cody's authority. McLaughlin took the news to Cody, who was back in the officers' club.

Nobody knows what may have befallen Buffalo Bill with a confrontation with Sitting Bull that day. McLaughlin saw nothing but potential trouble with the meeting and later congratulated himself, "My telegram saved to the world that day a royal good fellow and most excellent showman."

Sitting Bull's capture: Another appeal to the Indian Office, new orders from the military, and drawing the proper plan.

|

McLaughlin dreaded the idea that at any moment Miles may emit another decree. He had hoped for a cold, snowy winter which might curb the Ghost Dance. But just as Sitting Bull had predicted the hot summer that destroyed the crops, he also had predicted a mild winter that for the most part was "coming to pass." "Yes, my people," he announced back in October, "you can dance all the winter this year, the sun will shine warmly and the weather will be fair." However, a snowfall on December 5 gave McLaughlin a pretext for trying once again to head off the army. The next day would be ration day, when all but the most dedicated dancers would be at the agency.

"Weather cold and snowing," he telegraphed the Indian Office. "Am I authorized to arrest Sitting Bull when I think best?"

The reply came promptly: "Make no arrests whatever except under orders of the military or upon an order from the Secretary of the Interior."

That ceded entire control of the issue to General Miles. Angry over the Cody affair, he moved at once. Miles sent orders that reached Colonel Drum on December 12 to "... consider it his especial duty to secure the person of Sitting Bull using any practical means."

At the risk of provoking his commanders, Drum turned to McLaughlin, and together they plotted out the plan to arrest Sitting Bull on the next ration day, December 20, and it would be made by the agency's Indian police backed as needed by soldiers. McLaughlin and Drum summoned Lieutenant Bull Head and expained in detail the plan to be carried out by his Indian police force.

Later on the 12th, McLaughlin got word that Sitting Bull had been invited to the dance camp in the Stronghold at Pine Ridge, and he and his counselors had decided that he ought to go. Sitting Bull had his son-in-law compose a letter in English to McLaughlin which said, "I got to go to [Pine Ridge] Agency and know this Pray [take part in the dance]: so I let you know that ... I want answer back soon." McLaughlin strongly believed that Sitting Bull intended to go to Pine Ridge whether he gave permission or not. And now the career of Colonel Drum was on the line if Sitting Bull escaped. If that happened, General Miles' reaction was predictable. December 13, McLaughlin answered the old chief with a letter containing professions of friendship and more pleas to send the dancers back to their homes. "Therefore, my friend, listen to this advice," the agent wrote, "Do not attempt to visit any other agency at present."

On December 14, two of Indian police commander Bull Head's spies brought word that Sitting Bull and his followers planned to leave the next morning and would shoot any police who tried to stop them. Whether or not this rumor was true, McLaughlin and Drum agreed the arrest could not wait until ration day; it had to be made the next morning before daybreak.

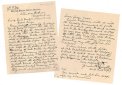

Major McLaughlin sat at his pine desk in the gloomy light of a cloudy December afternoon and grimly composed another letter of the utmost urgency. This one to the commanders of his Indian Police.

Lieut. Bull Head or Shave Head

Grand River

Dec.14,1890

(Will open up new window)

From reports brought by Scout "Hawk Man" I believe the time has arrived for the arrest of Sitting Bull and that it can be made by the Indian Police without much risk — therefore I want you to make the arrest before daylight tomorrow morning ... I have ordered all the police at Oak Creek to proceed to Carignan's school to await your orders. This gives you a force of 42 Policemen to use in the arrest.

Yours Respectfully,

James McLaughlin

U.S. Ind. Agent

P.S. You must not let him escape under any circumstances.

McLaughlin looked outside at the bleak, snowy Dakota landscape. He watched a small group of meadowlarks pecking for seed in the exposed grass by the agency livery.

Meadowlarks had spoken to Sitting Bull. Spoken to him of "a warning about the future," the old chief had told McLaughlin.

"What did you tell him?" McLaughlin somberly asked the birds.