October 1851 |

21 October 1851

Patrick McLaughlin was close to the front of the line as they waited for the medical officer to arrive on the docks. It was difficult for him to be patient this morning; he was anxious to board ship. He was so close to realizing his dream of starting a new life in America.

"Think he'll dock me for havin' this cough, Pat?"

Patrick looked at his good friend James Andrews, and saw his eyes filled with excitement. Patrick's own eyes felt tired; neither of them had slept most the night. He looked at James' bundle of provisions at his feet, and then at the tall ships lining the quays of Dublin. One of those ships will be their home for many weeks. Patrick was glad his buddy shared his dream.

"Naw. Just try'an keep from coughing," said Patrick. Patrick pointed to their sack containing the leftover loaf of bread they had shared since yesterday. "Chew on some bread."

The two friends were in their early twenties, each had survived the potato famine of the last six years while learning the craft of shoemaking. They had managed to save £3 (US $15) apiece for the tickets in steerage on the British Queen which was departing tomorrow from Dublin to New York.

The outside of the inspector's shack was plastered with ads selling tickets to America, ship schedules, government circulars giving advice on lodging and exchanging money, and letters from abroad printed in newspaper articles. One such article caught Patrick's eye. It was a letter written to the London Times last year by an Irish settler who for twelve months had been living in a place called Wisconsin.

(14th May, 1850)

I am exceedingly well pleased at coming to this land of plenty. On arrival I purchased 120 acres of land at $5 an acre. You must bear in mind that I have purchased the land out, and it is to me and mine an "estate for ever", without a landlord, an agent or tax-gatherer to trouble me. I would advise all my friends to quit Ireland - the country most dear to me; as long as they remain in it they will be in bondage and misery.What you labour for is sweetened by contentment and happiness; there is no failure in the potato crop, and you can grow every crop you wish, without manuring the land during life. You need not mind feeding pigs, but let them into the woods and they will feed themselves, until you want to make bacon of them.

I shudder when I think that starvation prevails to such an extent in poor Ireland. After supplying the entire population of America, there would still be as much corn and provisions left us would supply the world, for there is no limit to cultivation or end to land. Here the meanest labourer has beef and mutton, with bread, bacon, tea, coffee, sugar and even pies, the whole year round - every day here is as good as Christmas day in Ireland.

The door opened and within seconds they were inside the small, dimly lit shack. Patrick held on tightly to his ticket and bundle as those in line bumped into each other. The medical officer making the inspections was a surgeon appointed by the government. The line was moving fast and a clerk sitting at a table was quickly stamping tickets. The "inspection" took only one or two seconds. Ship owners were paying the officer £1 (US $5) for every hundred passengers inspected.

The officer said to each one, without drawing a breath, "What's your name? Are you well? Hold out your tongue. All right." and then addressed the next person. Patrick's and James' tickets were stamped -- James had neither time for a cough nor bite of bread -- and they headed whooping and laughing down the docks towards their new temporary home.

Passengers were entitled to board 24 hours before departure. After walking up the swaying gangway, each passenger's name, sex, age, and occupation were entered into the ship's manifest by the first mate. Patrick and James were among the first passengers to board the British Queen, not perhaps the best name for a ship carrying Irish emigrants fleeing the Famine. Queen Victoria, the stern-faced monarch, and her Parliament in London, stood accused of doing too little to save Ireland from her plight.

Patrick wanted to grab a berth below deck now while they had a choice, and down the hatch they went.

The British Queen was a 534-ton barque -- a medium-large sized ship of its time. A barque is a sailing ship with three masts, with the fore and main masts square-rigged, and the aftmost mast (mizzen mast) fore-and-aft rigged. This was an old but reliable vessel that had sailed for 66 years -- having been built in 1785. The decking below had been modified several times over the years according to its cargo. She had earned her owners profits by hauling goods from America, timber from Canada, and slaves from Africa. Over the last 6 years, the ship's hold had been fitted with bunks for human cargo -- to profit from the millions of desperate Irish emigrants fleeing the Famine.

The years of the Irish Famine, from 1846 to 1851, were marked by an urgency to get away as never before. The Irish arriving in New York averaged 300 per day for 6 years. The passages to America were marred by disease where frequently the mortality rate aboard reached 40 percent. Thus, the ships were often called "Coffin Ships." Ships had always sailed in the spring and summer. Now, the clamor for a passage saw vessels of every kind and size departing in the autumn and winter too. The Irish immigrants were brave, desperate people searching for a new life and willing to take their chances against the hardships aboard which included the worst of weather. The bitter cold, ice, gales, fog, storms and heavy seas, and short days and nights could not deter these desperate people.

A ship the size of the British Queen could legally carry 220 passengers in steerage according to the British Passenger Act of 1847. Infants, crew, and cabin passengers were not included in the count and children under 14 were counted as half a passenger. Stiff fines would await the captain upon arrival if he exceeded the limit and the law was enforced. A similar-sized American ship sailing under the American Passenger Act would allow up to 150 passengers with children being full passengers; their fares, however, were more expensive.

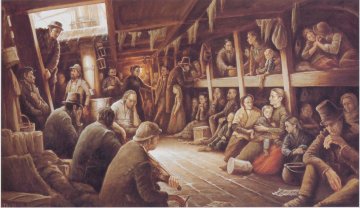

Below deck, Patrick stuffed his large bundle of possessions into a lower bunk close to the forward hatch. James climbed into the bunk above for some sleep. The bunks here were 4 tiers high; each bunk was 6 feet long, 2 feet wide, and 2 1/2 feet high. It was dark and dingy below deck and terribly warm. The odor of wet wood and mildew were mixed with the smells from the bilge and the livestock below, along with other unidentifiable sour and pungent odors. Feeling nauseated, Patrick climbed above deck into the fresh air.

The rest of the day, Patrick watched dozens of men, women, and children board the vessel. The items with which they would start their new life were pushed and pulled up the gangplank. Patrick watched as the ship's first mate forced a dressmaker named Mary Goss to abandon her spinning wheel on the dock. And Edward Lawless, a spoon maker, had to leave his anvil behind. Patrick was glad that the leather-working tools of his trade fit easily into his bundle.

Later that night, spirits were high below deck as the passengers settled into their cramped quarters. Daniel Sullivan played the fiddle while they sang and danced in the aisle late into the night.

22 October 1851

|

The ship was about to embark on their 3,000 mile journey and all passengers gathered on deck. The captain of the British Queen, Christopher Connay, busily shouted out orders to the crew while the first mate checked in the late coming passengers. Luggage and boxes were being flung aboard while men, women, and children were scrambling up the gangplanks. The British merchant flag named the Red Ensign -- red with the Union Jack in one corner -- was raised in the ship's aft. There was a fine breeze this morning.

"All hands ahoy!" shouted the captain. "Lay aloft and loose the topsails!" The crew sprang into action to unfurl and set the sails. "All ready forward?" asked the captain. "Aye, aye, sir, all ready," answered the first mate. "Let go!" "All gone, sir." The chain cable grated over the windlass and through the howsehole. "Let go aft!" Instantly the ship was launched and started moving out of port.

There were a large number of spectators at the dock-gates to witness the departure. Hats were raised, handkerchiefs were waving, and their were tearful shouts of farewell from both shore and ship.

Before hoisting the main sails and while the ship’s crew searched for stowaways below deck, Captain Connay took a roll-call of all passengers and prepared his list which would be handed to Immigration officers on arrival in New York. The total on board were 235 men, women, and children including 11 cabin passengers with an additional crew of 15 -- the captain, a first and second mate, 7 sailors, 2 apprentices, a carpenter, a cook, and a steward for the cabin passengers.

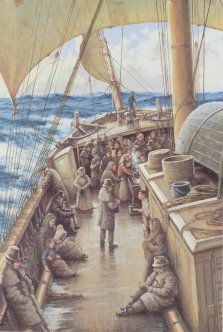

Several hours later, Patrick McLaughlin's thoughts were of his family back home as he gazed back at the emerald sliver of land slowly sinking into the blue sea. Standing on the rolling aft deck of the British Queen were most of the ship's passengers -- all savoring the last sight of land for weeks. The journey may take 40 days, maybe 60 days -- it all depended on the winds.

23 October

|

One day out. James Andrews and many others were seasick and moaning in their bunks. The air below deck was foul. One of the ship's rules was that only 20 or 30 passengers at a time would be allowed on deck where they could breathe fresh air, or to wash their clothing, clean themselves, or cook.

24 October

Patrick and James went above deck to cook their potatoes. Using a pot they brought along, they boiled the potatoes in a small amount of water on a hearth. The hearth was nothing more than a box lined with coals upon bricks. Each adult passenger was allowed only 6 pints of water per day to drink, wash, and cook. The ship was to provide each adult passenger, each week, with a total of 7 lbs. of bread, biscuit, flour, rice, oatmeal, or potatoes. Half-rations were issued to those under 14. Twice a week tea, sugar, and molasses were given out. One pound of food a day was really nothing more than an insurance against starvation. Ironically, this was often more than the half-starved emigrants had been eating for years prior to boarding ship.

25 October

|

Three days out and the winds had died considerably. Patrick could still see Ireland far in the distance. Rumor and the truth was that if the winds died and no progress was made early in the trip, they would turn around and limp back to Dublin.

26 October

There was no wind. There was a thick mist in the morning and the sea at noon was like glass. Those who were seasick were feeling better, but spirits were sagging. The captain and crew were in a foul mood and they and the passengers would take every effort to avoid each other. The crew gathered in the forecastle, away from the few dozen passengers allowed on deck. Patrick prayed for wind.

27 October

A breeze has sprung up from the southward. The captain ordered a fire drill. All adults formed a line on deck and passed buckets of seawater which were emptied on the imaginary fire. Fire, fanned by the wind, was a constant threat to an old wooden ship.

James' cough had been getting worse since boarding ship. When James doubled over from coughing from the exertion of passing buckets, he caught the first mate's ire. "You there," screamed Tibbits the first mate, "You sickly piece of useless scum! Get below and stay away o' you'll be the death of me!" James angrily started at Tibbits, then to Patrick's relief, he thought better of it and went below. The passengers feared that any disputes with the ship's crew could have tragic consequences.

31 October

To everyone's delight, this was the third straight day of very brisk winds. It was so windy the captain ordered all to stay below. The ship pitched, rolled, and creaked. It was Hallow E'en and there was song and laughter tonight. A turnip brought aboard that had turned moldy was carved with a scary face and then passed around. "'Tis ugly as Tibbits," James said of the turnip. The emigrant's spirits were high and they attempted to dance below deck tonight, but the roll of the ship made it impossible to keep one's feet. The songs continued well into the night.

"Far away-- oh far away--

We seek a world o'er the ocean spray!

We seek a land across the sea,

Where bread is plenty and men are free,

The sails are set, the breezes swell--

Ireland, our country, farewell! farewell!"

12 November

|

Strong winds have been out of the west for the last two weeks. Rumor was that the ship was not making good progress against the wind. The seas were very rough and most the time the emigrants stayed in their bunks or lie on the floor on top of bundles and chests; despite the lack of space, it was usually more comfortable there than on deck. Cold seawater would make its way below deck and dampen clothes and bedding. A few men from Limerick passed the time amusing themselves by creating rhymes. The rations were generally being eaten uncooked lately. The old ship creaked and groaned below. There were gaps between the planks of the floor of the hold. As they closed up with the movement of the ship, they would catch the women's skirts. Sometimes they would be pinned in one position for hours on end, until the ship shifted in the wind on to a new course.

Occasionally, the hatches would be closed, providing no ventilation below deck which made the putrid air worse yet. The grim news was out: several of the emigrants had the fever.

The fever aboard was typhus, one of the most contagious diseases in existence. The microorganism is carried in the feces of body lice and fleas which dries into a fine dust. The dust can be absorbed through the eyes or by being inhaled. The crowded conditions aboard the "coffin ships" were ideal for the rapid spread of the disease. Some of the passengers might have contracted the disease at home before they traveled. Once contracted, the survival rate was low, and death often followed within a few weeks.

23 November

|

The strong headwinds earlier in the month have been replaced by no winds. They were not making good progress westward. If this kept up, Captain Connay will be forced to reduce rations. The water was getting rancid. Three days of biscuits were served today. They were tough and somewhat moldy but everyone was so famished that they all ate them without complaint. There was many aboard now with the fever or dysentery. James and Mary Doyle's seven-month-old infant had died yesterday of the fever. When the captain found out, there was a quick burial at sea. Mary Doyle also had the fever. She was flushed, with a red rash and hollow-cheeked. Patrick was hungry, but fortunately had avoided contracting any disease so far. James Andrews' hacking cough persisted day and night. Patrick often offered James some of his water and bread but James didn't have much of an appetite.

27 November

The winds have remained very light. The captain has cut the meager rations in half. Even so, the rate westward was so slow, they were bound to run out of food and water before reaching New York. At this rate, they would be lucky to arrive before Christmas, which would make it an unusually long journey.

Rather than complaining, Patrick and James tried to make light of things which made them feel better. "I'm bettin' a pig wouldn't eat this stale biscuit, Pat," chuckled James.

"You're on -- pigs'll eat anything. Let's just see," said Patrick. They made their way to the livestock pen. Sure enough, the pig would not touch the biscuit, making them laugh.

"Get away from there you two!" hollered Tibbits as he suddenly appeared before them brandishing a rake. The two hurried off as Tibbits glared with a smile. "You'd better be stayin' away from my dinner!"

Safely back in their berths, James ate the biscuit.

The pigs and goats aboard were for the crew and 11 cabin passengers. Patrick wondered if the rations had been also reduced for the cabin-class with their white linen, fine china, and silver cutlery. Each member of the crew was still receiving 1 lb. of bread or biscuits per day, 1 1/2 lbs. of dried beef four days a week, 1 1/4 lbs. of pork on the other three days; goat milk, flour, peas; 1/2 oz. of coffee, 1/8 oz. of tea, and 1 gallon of water per day, and 1 lb. of sugar a week.

11 December

The ship's progress had remained slow with slack winds. This day marked the 50th day of the voyage. They had brought supplies for an estimated 50 day voyage, but were maybe 10 days from New York. The captain has reduced rations for even the crew, and all aboard now fear running out of food and water soon. Most passengers are weak and stay below -- their spirits and health are sinking. There have been two more deaths from the fever -- Catharine Smith, 50 years old, and her 4-month-old grandson Michael. The captain ordered the bodies on deck -- he never, ever came below. With a red sunset in the background, the captain read the funeral service for the dead and pitched the bodies overboard.

Patrick, weakened with hunger, forced himself to go on deck often. He searched and prayed for the sight of land.

17 December

|

The winds had been picking up for the last two days. Today there were strong, near gale-force tailwinds out of the east. The last of the provisions had been eaten, and the water-barrels were dangerously low. The ship was making good progress now in the heavy seas, and land was sighted ahead!

Everyone on ship was excited, and the encouraging news of the sight of land seemed to strengthen and inspire all. The word was that they were off the coast of Massachusetts and, in a day or two, would be safely berthed in New York harbor!

Patrick was delighted and thankful to be so close to his new home. As he watched the sliver of land appear occasionally over the high waves, he remembered the words of a famous American named Benjamin Franklin who had said,

"The only encouragement we hold out to strangers are a good climate, fertile soil, wholesome air and water, plenty of provisions, good pay for labor, kind neighbors, good laws, a free government, and a hearty welcome."It was these words and the lack of such an environment in Ireland that had inspired Patrick to make this journey.

However, the immediate climate was changing for the worse -- it was starting to snow. As Patrick watched, the sliver of America had disappeared behind a veil of heavy, blowing snow. The winds were now blowing strong from the north, and Patrick and all passengers were ordered below deck.

As the ship approached Nantucket Island, Massachusetts, the winds turned gale-force from the north. The full might of winter had descended on the ship. The British Queen was blinded by the snow and the air was filled with foam from the waves. The shore was shrouded in a blizzard.

|

Captain Connay carefully tried to maneuver the ship around Nantucket Island in the storm. Around the island lie dangerously narrow channels and shifting sand bars in shallow waters, creating a hazardous passage that was feared even by the most able mariners. Connay ordered little canvas aloft as he tried to navigate through the treacherous stretch of water. The ship was being blown too close inland and he fought hard to bring the ship into the wind. The ship rolled hard to starboard several times, throwing cargo and the fragile emigrants below to the sides of the ship. As the winds continued to increase and toss the ship, the captain ordered everything on deck battened down. The crew scurried frantically to secure the ship and reduce the sails. The look-outs on deck and aloft shouted for the captain to make adjustments to the wheel as jagged chunks of ice, bumping alongside, grazed the old timber hull. The northerly gale continued to blow the ship too close inland as darkness fell in the late afternoon.

The emigrants below could sense the dangerous situation above and were petrified with fear as they were thrown about in pitch blackness. "We're so close to being home, and now this!" moaned James to Patrick. Everything not fastened down was flying or rolling around. The ship would climb upward until it seemed she must fall over backward, then would pause for a moment before pitching forward with a plunge that threatened to rip the planks to pieces. The noise and confusion were terrifying. The running and shouting of the sailors; the flopping and ripping of canvas; the howling of the wind; the roaring of the waves as they washed over the deck and the load creaking and cracking of the ship's timbers all combined to drown the sounds of their screams below.

The ship straightened up and turned at a better angle to the wind. The terrified men, women, and children below crawled in total darkness to brace themselves against something secure. Patrick managed to crawl into a bunk; he wasn't sure whose bunk it was -- it reeked to high-heaven! Then, all was quiet below except for prayers being uttered.

Suddenly, the ship went aground.

As the ship's forward and downward momentum came to a jolting stop, Patrick was caught off-guard and almost thrown from the bunk. Unsecured items in the hold crashed all around them as the ship leaned peculiarly to starboard and did not roll back. Patrick strained to keep himself from falling across the aisle onto the moaning tangle of arms and legs. The hull shuttered and there was a tremendous ripping noise from below them.

The ship was aground in the ebbing tide off Muskeget, close to Martha's Vineyard, 12 miles from Nantucket Harbor. Captain Connay set the crew to work on several simultaneous tasks, calling out, "Lay out there and furl the jib! You there, check below and report back on any breaches in the hull! You two, man the bilge pumps -- we must lighten our load! You men, lower the fore masts and yards. Swing them overboard and secure them alongside!" On the chance that they could escape from the sandbar, Connay also ordered many heavy cargo items thrown overboard, but he retained their last barrel of water. The incredibly high seas prohibited them from hauling out and setting the anchors away from the ship in their boats to attempt to pull themselves off the sand. In addition, he received word that water was beginning to leak in through strained seams between the timbers of the hull. Connay abandoned any hope that they were going to move from this spot.

Below deck, Patrick and the others shifted to new positions along the side of the hold. They were uncertain about what had happened, and this terrified them. After being at sea for so long, Patrick sensed that the ship's motion was completely different now; instead of riding the waves, the ship was being shaken violently from side to side. It was getting cold below deck. The combined stench of stirred-up bilge water and livestock coming from below was overpowering. It was impossible to find one's belongings and extra clothes in the darkness, and all huddled together in their shabby clothes trying to stay warm. Blankets were passed around and given to the women and children.

The British Queen, stuck fast on the sandy seabed, was beginning to keel over dangerously as the tide subsided. The storm showed no sign of abating as the wind and waves twisted and pounded the ship. The temperature was dropping well below freezing. Connay and crew, wearing oilskins, scurried for protection in the forecastle as they watched black foamy seas build to the height of thirty feet before crashing down on the ship. Now time was the essence -- would anyone spot the stricken ship in time before she started to break up?

Below deck, the emigrants heard the blustering wind shrieking and rattling through the rigging above and the bump, bump, bump of ice floes bouncing off the exposed hull. The waves smashed in endless repetition against the deck and hull, each blow echoing through the ship like the thud of an axe on wood. When a tumultuous wave would shatter down against the ship, they felt and heard the ship shutter and splinter around them.

Patrick McLaughlin felt cold water under him. He put his hand down to touch seawater.

The ship was slowly filling with water.