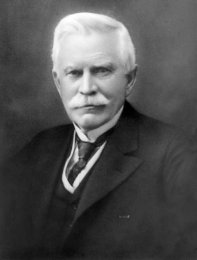

in 1915. Indian Inspector for the Interior Department. |

The procession of Indian police, soldiers, the dead and their families, and the injured drew slowly along the road on the Missouri River's high bank which lead to Fort Yates and Standing Rock Agency. It was noon on December 16, 1890. The procession had stopped at the police shelter last night when darkness had fallen, 20 miles away. A solitary old man on a pony rode in advance of the parade, moaning a mournful death song. Following, Indian women, riding in several worn farm wagons drawn by tired Indian ponies, keened in accompaniment. A contingent of police rode escort. Then, a wagon carrying the bodies of Sitting Bull and Indian police. Next was an army ambulance with a red cross painted on each side panel.

Following were army officers and two troops of cavalry trotting up the road. They angled left into the post, and drew up at the stables. An infantry column brought up the rear.

After the police dead were placed in the agency meeting hall, the wagon returned to Fort Yates to unload Sitting Bull in the dead house behind the post hospital. That night some of the older soldiers, veterans of the years of warfare with Sitting Bull's Sioux, went to view the body.

In the hospital, surrounded by weeping attendants and officials, Shave Head lay in the agony of an abdominal wound. He knew he would die.

"Did I do well?" he asked the Indian agent James McLaughlin. McLaughlin could only nod.

"Then I will die in the faith of the white man and to which my five children already belong, and be with them. Send for my wife, that we be married by the Black Gown before I die."

McLaughlin hurriedly sent a courier on a wagon for Shave Head's wife who lived eighteen miles from the agency. She arrived fifteen minutes after he had died in the arms of a Catholic priest in the early morning of December 17. Crumpled in the doorway to the hospital, she sang the Indian death song.

|

Bull Head struggled and thrashed in a coma until dying the following day.

Later, Indians and whites crowded into the little frame church of the Congregational mission south of the agency, where Catholic and Protestant divines conducted joint funeral services for the policemen. Then the people walked to the cemetery next to the Catholic mission church at the agency. A company of infantry snapped to attention and fired three volleys over the graves. As the coffins sank into the ground, the notes of "taps" mingled with the mourning wails of the Sioux.

Of the wounded, only Private Middle survived. Surgeons amputated a foot, and he recovered.

As the ceremonies concluded, McLaughlin opened the cemetery gate and walked slowly to Fort Yates. At the post cemetery, he joined three officers who stood at another open grave. On the bottom rested a rough wooden box that contained the canvas-wrapped remains of Sitting Bull. As a "pagan", he did not qualify for burial in the Catholic cemetery, and besides, the Indian police objected. A detail of four soldiers -- prisoners from the guard house -- shoveled dirt into the hole.

Sitting Bull's secret of the meadowlarks.

James McLaughlin, with assistance from interpreter Primeau, expressed his heart-felt condolences to Sitting Bull's wives in a tearful private meeting. His eldest wife, Seen-by-the-Nation, her head bowed with anguish, declared to James, "It was meant to be."

"How so?" asked James.

"I was his best friend as well as his wife," she said mournfully. "He told me of his hurts, and dreams, and visions. What he would tell me, no other man or woman would know. He told me visions of drought, of hard times for the Lakota, of much death for all red men. All have come to be."

"What he told me once, I did not understand," she continued. "He told me he heard voices in the field. It came from his friends, the meadowlarks. Meadowlarks were always wise counsel for he and our people. The meadowlarks in the field had spoken to him with great warning."

James thought back to the several obscure comments made by Bull two months ago in his office. Swallowing hard, he listened to the unveiling of Sitting Bull's secret.

"He... ," Seen-by-the-Nation choked as she struggled for composure. "He said the meadowlarks warned him: 'Lakotas will kill you'."

The words fell like blows to James' head.

"He tried to forget it -- but could not. From that time on," she tearfully recalled, "he seemed to feel he would be killed by his own people."

"And so," she sobbed, "it was meant to be, it came to be."

The aftermath.

After the Grand River shootout, word was passed through the Ghost Dance community that the troops were returning to base and no harm would come to them. Many attached themselves to the funeral column that headed north to the agency. Days later, prompted by couriers dispatched by McLaughlin, many more sought the security of the agency.

|

However, 372 other survivors of the shootout quickly packed up their families and traveled rapidly south where they joined up with chief Big Foot in southern South Dakota. Unfortunately, Big Foot had earned himself a place on the list of troublemakers the government thought should be removed. Orders came from General Miles to pursue and apprehend the fugitives. The army, under the commands of Colonel Forsyth and Major Whitside, caught up to Big Foot and his followers heading to the Ghost Dance stronghold in the badlands. The troops numbering 470 hurried the band southwest to Wounded Knee Creek in Pine Ridge Reservation and took up surrounding positions as the Indians set up camp.

On December 29, as the Seventh Calvary, Custer's old outfit, attempted to disarm Big Foot and his band, tensions rose to the flashpoint and exploded in the bloody maelstrom of Wounded Knee. During the slaughter that followed, Big Foot and over 300 Sioux men, women, and children were killed.

On January 15, 1891, Kicking Bear, the leader of the remaining dispirited group of Ghost Dancers, placed his rifle at the feet of Bear Coat: General Miles. The massacre at Wounded Knee effectively squelched the Ghost Dance movement and ended the Indian Wars, while poisoning relations between Indians and whites for generations to come.

"Sitting Bull had been murdered," charged the friends of the Indians throughout the nation. There flew allegations that McLaughlin and Drum had quietly instructed the police to bring in a corpse, and the soldiers had stood by to make certain they did not fail in their duty.

McLaughlin could not have been more astonished at the furor that burst over his head, nor more angry at the wild stories hurled back and forth by the press. Instead of protesting the outcome, he felt, the public ought to be pouring out its gratitude to the men who had laid down their lives in the cause of progress. James McLaughlin weathered the storm and went on to become a highly regarded Indian Inspector for the Interior Department.

In 1910, McLaughlin wrote the book My Friend the Indian, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1910). It is an autobiographical sketch of his work on the Standing Rock Reservation which contains a series of comments on Dakota life and history. The activities in which he was involved, such as the death of Sitting Bull, are dealt with in considerable detail.

Sitting Bull's gravesite at Fort Yates was vandalized several times over the following five decades. Then in 1953, an expedition of Sioux Indians swooped down on the gravesite in the dark of night and reportedly carried the remains of Sitting Bull to a new gravesite beneath concrete on the Missouri Valley heights opposite the city of Mobridge, South Dakota.

Analysis and Opinions

|

"The following graphic and reliable account of the death of Sitting Bull and of the circumstances attending it will be read with

interest by many readers. It was written by Major James McLaughlin, who for many years has occupied the post of Indian

Agent at Standing Rock, Dakota, and was sent to us by my request. Agent McLaughlin is a good example of what an Indian

Agent should be -- experienced, faithful and courageous. The report which he has so kindly sent us..." |

Despite McLaughlin's bright reputation, the historic record is peppered with enough allegations of assassination or murder to require a retrospective look at the question. It is twofold. Did McLaughlin order, or otherwise convey his wish, that Sitting Bull not be brought in alive? And even if he did not, did the police seize on the occasion to even old scores or remove a troublesome irritant from the Standing Rock community?

If McLaughlin used the police as a murder squad, either explicitly or implicitly, no compelling evidence survives to convict him. He cannot have been too sorry over the death of Sitting Bull, but he certainly was not prepared to risk the lives of his policemen for it. Confinement of Sitting Bull in some distant prison suited McLaughlin's purposes fully as well as death, and without much doubt that is what he intended.

The most persuasive refutation of the charge against the police lies in their own actions. However badly they handled the arrest, they clearly made every possible effort to get their prisoner out of the Sitting Bull settlement alive. Only when fired on and when the two senior officers were cut down did Bull Head and Red Tomahawk ensure, as the agent had ordered, that under no circumstances was Sitting Bull to be allowed to escape. As Captain Fechet pointed out in his official report, "If it had been the intention of the police to assassinate Sitting Bull, they could easily have done so before his friends arrived."

Another question for history is whether Sitting Bull's arrest and removal were justified. From the attitudes and perceptions of the civil and military establishments, their standpoint was that it was completely warranted. The militant feature of the Ghost Dance -- bulletproof shirts, the millennial interment of the entire white race -- decreed that any potential troublemaker be removed from the theater of war.

Sitting Bull was not planning to travel to Pine Ridge to make trouble but "to know this pray" -- to investigate the Ghost Dance at its source among Sioux. But then again, he would not have gotten there. His departure from Standing Rock, however peaceful in intent, would certainly have set off the same military scramble that Big Foot's actions did, with consequences possibly similar to Wounded Knee.

To Indians practicing the very principle of religious freedom that the white people celebrated, the government's reasoning to remove Sitting Bull or stifle the Ghost Dance made no sense. If white people could travel for spiritual purposes, why should not Sitting Bull enjoy the same privilege? Moreover, if whites could choose among all the mutations of Protestantism and Catholicism, so the Indians should have the same right to choose between them or, if they wanted, a Ghost Dance religion that drew on Christian principles. If whites could be suffered to predict a second coming or any other kind of millennium, including apocalypse, why should not the Indians be indulged a similar anticipation?

In historical hindsight again, with or without Sitting Bull's influence, the only thing likely to have triggered violence with the Ghost Dancers was military aggression. Left alone, the dancers would probably have danced until the movement collapsed, either when the Messiah failed to appear in the spring or, more likely, when cold and hunger dampened their fervor.

In retrospect, neither Big Foot nor Sitting Bull, if allowed to proceed unhindered to his destination, was likely to have provoked violence -- certainly not on the scale of Wounded Knee. McLaughlin and the decision makers however, dealt in prospect, not retrospect, and in that contemporary climate they harbored no doubts about the wisdom of their decision to arrest Sitting Bull.

Marie Louise Buisson McLaughlin

|

James' wife, Marie Louise Buisson, called Louise or Lou by her family, was born December 8, 1842, in Wabasha, Minnesota. Louise's grandmother was a full-blooded Sioux Indian. Her father, Joseph Buisson, born near Montreal, Canada, was connected with the American Fur Company, with headquarters at Mendota, Minnesota. She married James McLaughlin in Mendota, January 28, 1864. The couple had five children and also adopted a one year old Indian girl. Their son Charles was elected sheriff of Sioux County, North Dakota in 1916.

|

"In loving memory of my mother, Mary Graham Buisson, at whose knee most of the stories contained in this little

volume were told to me, this book is affectionately dedicated..." |

Having been born and reared in an Indian community, she acquired a thorough knowledge of the Sioux language. Having lived on Indian reservations with her husband for many years, she became very close to the Indians and had exceptional opportunities of learning the legends and folk-lore of the Sioux. Louise made careful notes of the legends, knowing that, if not recorded, they would be lost to posterity by the passing of the primitive Indian.

Louise wrote a book in 1916, Myths and Legends of the Sioux, (Bismarck, North Dakota: Bismarck Tribune Company, 1916), which retells these stories. One of the stories, "The legend of Standing Rock" tells how Standing Rock Reservation got its name.

Both Louise and her husband were strong advocates of education for Indians. While her husband traveled on Indian affairs business, she stayed on the reservation and was a Field Matron, a position in which she instructed Indian women on cooking, cleaning, and other home management issues. She also spent much time visiting the ill. During the rocky times of 1890, the protestant missionary Mary Collins wrote that the agent "and his wife were wearing themselves out working for the Indians." Louise died a year after her husband, in 1924.

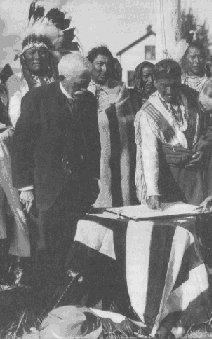

Indian Inspector for the Interior Dept. witnessing Sitting Bear sign the Declaration of Allegiance to the U.S. government in 1913. |

McLaughlin as Indian Inspector for the Interior Department.

McLaughlin was promoted to Indian Inspector for the Interior Department in 1895. In the new position, he was instrumental in initiating the American Indian policy reform movement. In 1909, McLaughlin was a key figure in the last great Indian council, participated in by eminent Indian Chiefs from nearly every tribe in the United States. The dominant theme of the council was "peace" between fellow Indians, and all men. The success of the Council led Congress and President Taft to pass a bill on December 8, 1911 for the erection of a National Indian Memorial (in the harbor area of New York). The dedication of the memorial was held on Washington's birthday in 1913, attended by 32 Chiefs representing all Indian Nations.

It was here that the first page of the "Declaration of Allegiance" was signed by the Chiefs and the President. The consensus by the Chiefs was, that for the first time they felt that they were part of this country. It was then suggested that all the tribes be given the opportunity to sign the same pledge of loyalty. McLaughlin organized an expedition of citizenship to all the tribes to attempt to obtain signatures from all who wished to sign. The expedition took seven months, covering 27,000 miles by train, boat, stagecoach, automobile, horseback and donkey. Every tribe, without exception, signed. It is the only document ever signed by all native American tribes in the United States. The document is signed by over 900 Chiefs, far more leaders than any other document in world history. These leaders represented 189 tribes who were at one time considered as independent Nations. The Declaration is the first voluntary acknowledgement of the sovereignty of the United States over all American Indian tribes.

|

For the next ten years, McLaughlin was instrumental in persuading Franklin Lane, Secretary of the Interior under President Wilson, to speed the granting of citizenship to qualified Indians. McLaughlin designed tokens of citizenship that were presented in 1916 and 1917. These consisted of a purse ("The wise man saves his money, so that when the sun does not smile and the grass does not grow, he will not starve," observed the presenter), a leather bag, and a button. At a 1917 ceremony back on Standing Rock Reservation, McLaughlin witnessed Indians shooting symbolic "Last Arrows".

Laboring long past the retirement age, McLaughlin died in office in 1923, at the age of eighty-one. One year later, on June 15, 1924, full citizenship rights to every American Indian was granted by the Act of Congress.

James was buried in McLaughlin, South Dakota on Standing Rock Reservation -- a town he helped found and named after him, incorporated in 1909. An annual summer event in McLaughlin to this day is a rodeo named the "Major James McLaughlin Stampede." Here, a century after brutal warfare and many diplomatic obstacles, rivals of different colored skins duel in an entertainment arena, rather than on the battlefield.